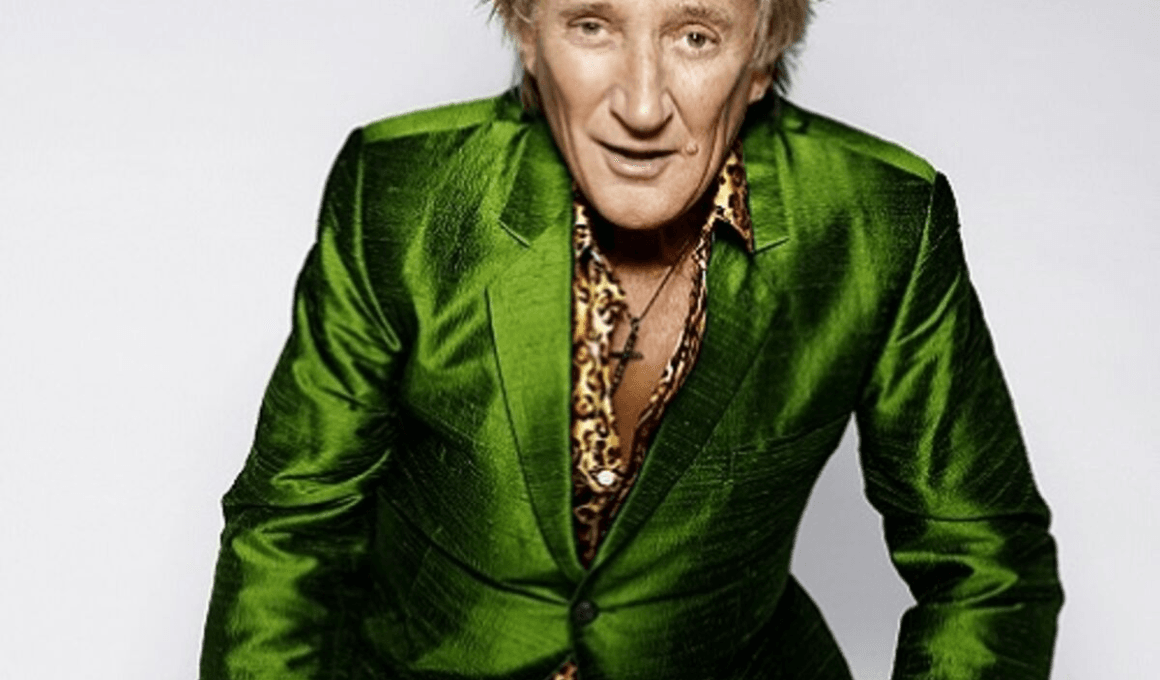

Gather ye near, and hearken to the tale of Sir Roderick of House Stewart, the bard whose gravelled voice stirred the hearts of millions, whose feet once danced upon the muddy grounds of London’s humble quarters, and whose fame would echo through the annals of song.

Yet beneath the crown of gold records and the thunder of cheers, the minstrel bore a burden he dared not name for many a year. In solemn candour, now as age wearies his frame, he hath confessed:

He, the voice of an age, was a child of letters lost — a soul entangled in the snares of dyslexia.

Of Youth and Mockery

As a stripling lad, young Roderick David was scorned by his tutors, called “dull as two short planks.” The letters upon the parchment mocked him cruelly, “dancing like drunken footmen,” he did say. Yet from the jeers of the classroom, he found escape — upon the football pitch, where his nimble stride brought him near the halls of sportly glory, and within the melody of records, where Elvis and Little Richard taught him that one need not read to feel the rhythm of life.

Of Fame and Hidden Craft

When the world did first echo with the strains of Maggie May, few knew the clever arts Sir Rod wove to cloak his struggle:

- The Ritual of Repetition: Lo, he demanded his scribes and musicians play demo songs again and again — fifty times or more — until every note and word was etched within his soul.

- The Signature’s Secret: The famed flourish of his name, beloved by fans, did hide the truth — that spelling was a foe he never vanquished.

- The Enchanted Scrolls: In concerts grand, hidden scrolls with giant script and markings bold were placed ere him — a magician’s trick, masked in stagecraft.

Of Legacy and the Heir

The true turning of the tide came when his own son, young Liam, was beset by the same affliction. In the boy’s trials, Sir Rod saw his own shadows return. And by the grace of his lady wife, Penny the Gentle, who now liest his “eyes for fine print,” he found courage not just to endure, but to give.

He hath now pledged his coin and his name to a noble cause: the founding of a music hall in London, where young souls afflicted as he was may find solace in song and healing in harmony.

Of Song and Soul

Historians now whisper in learned halls that the bard’s famed growl, that voice both rasp and roar, may have risen as a gift from struggle — a way the soul learned to speak when the mind could not. Each ballad, each performance, was not mere revelry, but a man’s cry to be known and understood.

And now, as Sir Rod readies his final tour through the kingdoms of men, he speaks not with rhyme nor rhythm, but raw truth:

“Those golden discs? Each one is my answer to those who deemed me nothing. My vengeance — sweet, melodic, eternal.”

And with a wink, he jested as only minstrels can:

“By thunder, if I knew that speaking plain would bring such cheer, I’d have done so after my first hundred million songs.”

Thus ends the telling of this tale — not of sorrow, but of triumph. For in the voice of Rod the Minstrel, we see the truth of the old wisdom:

Even the broken quill can write the grandest tale, when guided by a heart unshaken.